After finishing his studies as an orthoprosthetic technician, Martin Kaufmann began working “with humans” in different clinics in the American Midwest. But it wasn’t until his cousin’s dog suffered a stroke, and the subsequent loss of mobility of one of his paws, that he realized how limited the options were to cure an injury that he was fed up with treating in humans.

“I was surprised to hear veterinarians consider complete limb amputation,” Kaufmann says. “It was that that led me to ask the most obvious question: why don’t our favorite quadrupeds enjoy the same access to prosthetics?”

Why don’t our favorite quadrupeds enjoy the same access to prosthetics?”

Human prostheses have been common for centuries, but until recently the only options available for animals with total or partial loss of their limbs were euthanasia or complete amputation. Kaufmann was able to verify that most veterinarians did not even consider prostheses as an option; that was simply not part of the educational baggage.

“Unlike in the case of surgeons and doctors, that was not part of any training module,” he says. “No one had published any studies explaining that dogs could use prostheses.”

This lack of data is a problem. There are very few researchers dedicated to animal prostheses and not enough published studies to ensure that animals could, or in what cases, benefit from the use of a prosthesis. Not even to say for sure that the prostheses would not cause them any harm.

The dog ‘Journey’. / KEVIN BACHAR.

One of the main points of debate is to clarify, once and for all, whether a prosthesis hinders or helps those animals that have lost a single leg. A dog with three legs, when playing in the park, may very well appear happy — which doesn’t mean it’s not facing a challenge, Kaufmann says. “Only the cardiovascular endurance needed to carry out the simplest or most trivial activities is already enormous,” not to mention the possibility of causing new injuries.

“More appropriate for the use of prostheses will be those animals with two damaged limbs, because quadrupeds are not good at walking on two legs,” says Denis Marcellin-Little, a professor of orthopedic surgery at North Carolina State University School of Veterinary Medicine. “With three, the matter is even more debatable; some carry it much worse than others.”

You can’t ask a dog his opinion about the latest adjustments… All decisions will be based on clinical evaluation and data.”

Even with prostheses, there is still the challenge of getting the animal used to its use. “One of the main factors of failure with pet prostheses appears when [el animal] it fails to explain what is that thing that is stuck there,” says Marcellin-Little.

Communication problems are the bread and butter of any prosthetic technician, especially if the device is uncomfortable or unstable. “You can’t ask a three-year-old to give you their impressions about the assembly and operation of a prosthesis,” Kaufmann says, “[and] you can’t ask a dog his opinion about the latest adjustments… All decisions will be based on clinical evaluation and data.”

The enormous diversity of sizes and anatomies between different animals is yet another challenge: having to memorize a whole new set of musculoskeletal concepts is, to say the least, problematic. Kaufmann asks, “How are you going to be able to give the patient the quality of life they deserve, when you have to learn things like, ‘Let’s see… how does this stork work? What’s normal for a stork?'” There are also important physiological differences to take into account. For example, in Thailand, in 2007, an elephant was fitted with a prosthetic leg after having stepped on a mine in its infancy. “Elephants sweat by the limbs to regulate their temperature, like most animals, so the use of a prosthesis can interfere with their thermal management. In the case of the elephant, this caused it to beat its ears more frequently, to compensate.”

It’s been 12 years since Kaufmann and his wife Amy opened Orthopets, a company dedicated to the manufacture of veterinary prostheses and orthoses (prostheses replace lost parts of a body, while orthoses protect or support injured limbs). With large dogs it’s easier, he tells us — they’re about the size of a preteen child — but most Kaufmann canine patients bulge less than a two-month-old baby. “You end up trying to put a prosthesis on a kilo dog that circles around you like a madman.”

‘Molly’, a pony missing a leg. / LIZETTE GESUDEN

Meanwhile, new cases of animal prostheses appear more and more frequently in the media. Only in recent years have we had the Dudley duck, with a 3D printed leg; Beauty, an Alaskan bald eagle with a prosthetic beak; and Smaug, a Komodoequiped dragon with an orthosis that prevents him from walking with the instep of his foot. Marcellin-Little recently fitted an orthopedic corset to a sea turtle that had a damaged fin. This way he could keep the limb stable during the healing process.

There is no shortage of challenges: “What solution can you offer a dog that, after losing part of each of its legs, walks, basically, in a dive?” asks Kaufmann. “[Es] incredibly complex”. However, addressing these challenges could reveal or refine techniques that will later be useful for both animals and humans – such as prosthetic implants, where a prosthesis is fixed by a rod inserted directly into the bone. “With animals we can go much deeper than we would be able to – or are allowed to do – with humans,” Kaufmann says. If this technique were to be perfected, it could mean the practical overcoming of suspension problems in traditional prostheses.

Source: newspaper “El País”

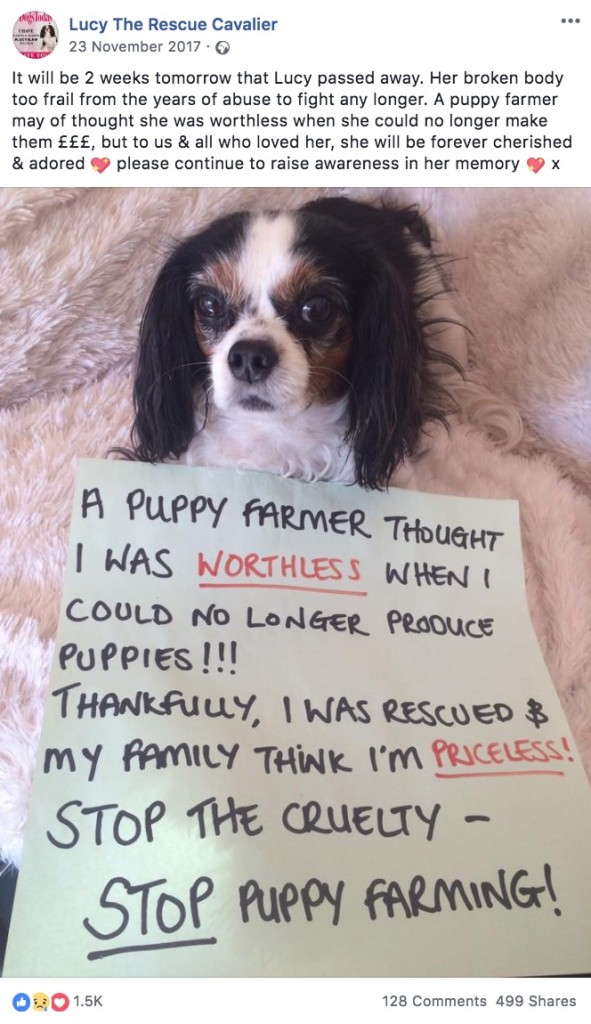

In the United Kingdom, the ”

In the United Kingdom, the ”

The dog ‘Journey’. / KEVIN BACHAR.

The dog ‘Journey’. / KEVIN BACHAR.